by Hanna Barbara Coltman

17th July 2020

The distinctive gravelly smoker’s voice, tinged with its slight East End timbre crackled over the phone –

” Do you still have the marble slab?”

Alas, I had to confess that the slab, which had stood propped up behind the the redundant butler sink now serving as a pond on the rockery garden, had, at some point, fallen over and a corner had broken off. Before I had time to explain that it was gathering moss in some corner of the garden, the line went dead.

That was the last time I heard from my extraordinary friend, Suzanne Lang, the talented potter, who perfected her art of throwing pots at the side of Bernard Leech and whose witty political and social comments were displayed on her majolica style pottery collected by both the British and the Victoria and Albert Museums as well as collectors world wide.

She died on 28 March 2011, her obituary appearing in the Guardian and on the BM site.

Suzanne, who had spent most of her life in the East End, had, at some point, picked up slabs of marble from the local junk shop intending to use them for rolling out clay. Always generous, she offered me the one with the two stanzas from Byron’s Childe Harold and, I presume, another two would have been distributed to friends, leaving her one to work on.

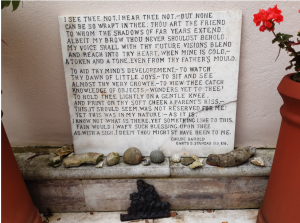

A couple of months ago, as the Covid 19 lockdown took its toll, I found myself spending more time in the garden and came across the damaged slab. Cleaned of its moss coating and splashes of concrete from careless builders, I was able to pick out the lettering, which revealed the two stanzas 115 and 116 from Canto III of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. On careful reading it shows that the first 2 lines of stanza 115 were left out:

My daughter! with thy name this song begun –

My daughter! With thy name thus much shall end –

Further more, two extra lines from stanza 118 were added the end of stanza 116

Fain would I waft such blessing upon thee

As with a sigh, I deem thou might’st have been to me!

I have to confess I knew little of Byron apart from Caroline Lamb’s famous quote that he was ‘Mad, Bad and Dangerous to know.’ And that he died fighting for the Greek cause at Missolonghi. As I worked on the lettering I began to research where the monument to Allegra, as I assumed it to be, could have come from. I immersed myself in his story, and that of of Allegra’s pitifully short and unhappy life. As Byron himself put it:

The child of love, – though born in bitterness

And nurtured in convulsion.

An answer did not easily present itself. There is a plaque to Allegra at the entrance to the Convent of St Giovanni, celebrating her brief stay there, whilst her father was conducting a love affair with the Countess Teresa Guiccioli in neighbouring Ravenna, dismissing the poor child’s appeal to visit her. The plaque reads:

In questo convento di S. Giovanni Battista

GG Lord Byron il 22 gennaio 1821 poneva educanda sua figlia Allegra.

La visitava nell’agosto P.B. Shelley travandole bella e felice

non presago che il 20 aprile seguente morte l’avrebbe rapita di 5 anni e 3 mesi

al bramoso affetto del grande genitore.

Well, at least Percy Bysshe Shelley, whose wife Mary was Allegra’s mother’s step sister, took the trouble to visit Allegra in the convent to check on her well being.

When Allegra died, Byron was overwhelmed with grief. The daughter, when alive was a nuisance to him, now dead, he was distraughtto an unimaginable degree considering how he ignored her in life. He sent her body to England, making arrangements to have her interred in a grave at St Mary’s Parish Church, Harrow, Middlesex. His favourite spot with a view was near the Peachey Tomb which inspired, ‘Lines written beneath an Elm in the Churchyard of Harrow’. The words are reproduced on a memorial in front of Peachey Tomb erected by a son of one of Byron’s school friends in 1905.

Byron’s request to place a memorial plaque to Allegra was ignored. This is what he intended:

In memory of Allegra, daughter of G.G. Lord Byron,

who died at Bagna Cavallo in Italy, 20 April 1822,

Aged 5 Five Years and Three Months

‘ I shall go to her. But she shall not return to me’

2 Samuel, XII:23

The vicar of the day, appalled by Byron’s scandalous reputation at the time, also ignored his wishes for Allegra to be buried on a plot of his choosing and shamefully Allegra’s body was laid to rest in an unmarked grave outside the door of the South porch. In 1980 The Byron Society placed a stone bearing the words:

In memory of

ALLEGRA

daughter of LORD BYRON

and CLAIRE CLAIRMONT

born in Bath 13-1-1817

died Bagnacavallo 19-4-1823

buried nearby

Erected by the Byron Society

Having followed the trail of Allegra’s short life in Italy and her burial in Harrow, I then turned my attention to Bath where she was born. No sign of any memorial to her. It was at that time I contacted the Byron Society to see if they could shed light of the history of the quotation on my marble slab.

Just After I sent off my email I had a EUREKA moment!

Could it be that the memorial was to a much loved child born in the East End of London. The memorial may have been bomb damaged in the second World War or indeed, as we have witnessed since, to make space for the living, many church yards have been cleared of tomb stones and monuments and turned into parks and recreational places for children. So, could not the slabs have come from such a source? A monument to a beloved child of a well to do East End Family recording her sad passing and nothing to do with Allegra.

I then thought back on my friend, Suzanne’s frantic call, made shortly, I suspect, before she died in 2011. Perhaps she wanted to reconstruct the memorial. In which case, on one of the other 3 slabs would be a child’s name, the date of birth and the date of death.

That seems to be a plausible solution to the enigma of Childe Harold verse which now has pride of place on my patio in North London.