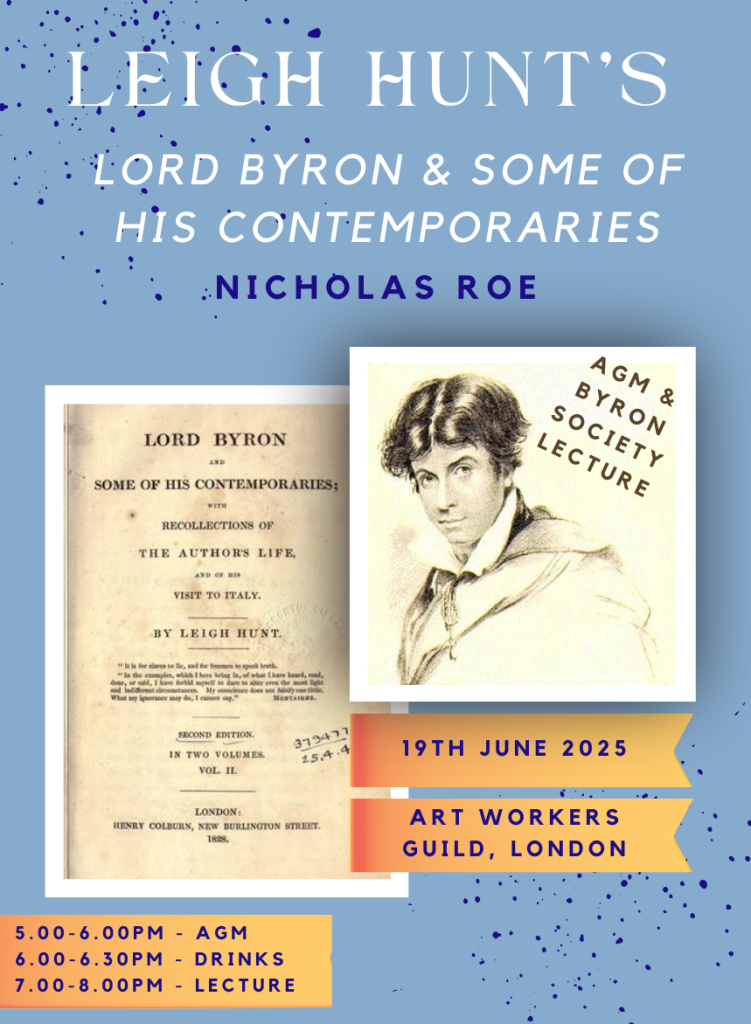

From John Lockhart to critics and biographers of our own time, Leigh Hunt’s Lord Byron and Some of his Contemporaries (1828) has been disparaged and dismissed — ‘the miserable book of a miserable man’. So routine has this become that one suspects most have not bothered to read what Hunt’s book actually says. Opening with Marilyn Butler’s chapter ‘The Cult of the South: the Shelley circle, its creed and its influence,’ I want to consider how the ‘Marlow moment’ of Spring 1817 and its reveries about the Mediterranean shaped the classicism of Hunt’s Foliage (1818) and, more particularly, the narrative of Lord Byron and Some of his Contemporaries (1828). I aim to explore Hunt’s book from several perspectives: as a corrective to the idealistic ‘Cult of the South’ and to some ideas about Byron, and as a narrative that prefigures modernist experiments. We are all aware of Hunt’s prized independence as editor of the Examiner, so perhaps we should reflect on Hunt’s words: ‘I am not vindictive’, ‘I tell the truth’. What will emerge in the paper, I hope, is a more nuanced view of Lord Byron and Some of his Contemporaries as a prototype of modern biography, published long before Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians (1918) spurned ‘tedious panegyric’ and promoted biography that would shoot ‘a sudden, revealing searchlight into obscure recesses.’ As Hunt came to terms with Lord Byron and the actuality of ‘the South,’ the ‘Marlow moment’ can be seen to have helped to shape Hunt’s determination to ‘put an end to a great deal of false biography’. That this meant Hunt would have to write ‘of necessity a painful retrospect’ is one compelling aspect of a complex and self-critical narrative that tells us of ‘a sense of mistake on both sides’.