By Jim Potts, 11th April 2020

Byron’s spirit and influence follow us around, even when we’re not consciously walking in his footsteps.

At my school, Shelley’s poetry was on the ‘A’ level English syllabus (even though much of his poetry had been trashed by F.R. Leavis). Lord Byron didn’t get a look-in. At university I discovered Don Juan, which made a delightful change from Paradise Lost, the Aeneid and Beowulf.

It wasn’t until I was posted to Greece in 1980 that I became conscious of how central Byron’s work had become to the literary canon (my canon, at least – but I also accorded a deservedly high place to the Dorset dialect poet, William Barnes). Childe Harold, Canto II, accompanied me on most of my travels in Greece, to Epirus and especially to Ioannina, Zitsa, Cephalonia and Missolonghi. I had taught in Corfu in 1967-1968 and visited Ioannina in 1968, where I’d first became interested in Ali Pasha.

In 1984, I organised a public reading by Yannis Ritsos in Thessaloniki. He had accepted my invitation to help celebrate the 50th anniversary of The British Council He began the evening by reading a Greek translation of Byron’s moving poem, “On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year”.

In 1986 I was posted to Czechoslovakia. Shelley was officially approved by the Communist Party in Eastern Europe (especially in the GDR, as Professor Dr.sc. Horst Hőhne, the distinguished Shelley scholar, confirmed on November 5, 1989, when I visited the Wilhelm Pieck University in Rostock, only days before the fall of the Berlin Wall, which I witnessed on the spot).

Byron was still being taught and translated in Czechoslovakia (see Dr. Martin Procházka exhibition poster). Michael Foot came out in his private capacity to give a talk on Byron at Charles University in Prague.

The British Council’s work in facilitating visits by writers and academics was widely appreciated. As a farewell tribute, and unbeknownst to me, three distinguished Czech poets translated sixteen of my poems and somehow managed to have them published in a limited bilingual edition by the time of the launch and reading in October 1989, before the Velvet Revolution.

It was only much later that I discovered Byron’s play, Werner, with its Prague connections.

I was a member of the Byron Society from 1982-1989, but pressures of work and frequent travel to overseas destinations kept me busy after that. In the course of a seven-year posting to Australia (from 1993), I gave a talk on travel writers on Greece (Byron, Durrell and Lear) and renewed my acquaintance with Sir Charles Mackerras (whom I’d met in Prague). He generously agreed to support a scholarship for young Australian composers and conductors. He also introduced me to the compositions of his ancestor, Isaac Nathan, who’d invited Lord Byron to collaborate on his Hebrew Melodies project. He’d asked Byron to write a few poems for the melodies (Byron wrote 26 lyric).

I lent my precious twelve-volume edition of Byron’s Letters to an Australian novelist. I was glad to get them back, eventually.

In 1991, I was invited by the Ministry of Culture to visit Albania, with a view to re-establishing cultural relations between Albania and the UK. On a return visit I went to Tepeleni.

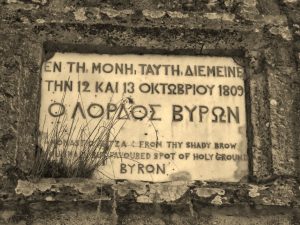

In September, 2003, I participated in a symposium in Delphi, Greece, where Tony Harrison took a small group of us to find the faded, scarcely-visible carved inscriptions of Byron and Hobhouse on a fallen column.

Byron in Delphi, Tony Harrison

Led us to the spot

At the Temple of Athena Pronaia.

It took a while to find it,

The fallen column

With the faint inscriptions:

BYR.., HOBHOUSE.

Perhaps we would be

The last to see them,

Where Philhellenes

Had carved their names

Near the navel of the world.

He poured on water

From the Castalian Spring,

Used a mirror

To make more distinct

Their Delphic markings.

Our secret mission, in search of scratches.

BYR…BY….B….a B, maybe?

The time may have come for more armchair travelling. Scholars seem to have discovered almost every aspect of Byron’s life and work, but there is always something new to discover, or to rediscover, for the interested individual.

I’d like to finish by quoting from a poem by Adrian Mitchell, Byron is One of the Dancers.

His poems – they were glad with jokes, trumpets, arguments and flying crockery

Rejoice

He shook hearts with his lust and nonsense, he was independent as the weather

Rejoice

Alice, alive, fully as alive as us, he used his life and let life use him

Rejoice

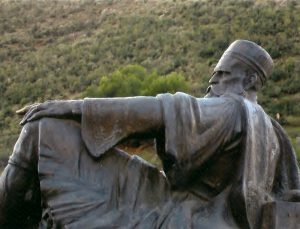

He loved freedom, he loved Greece, and yes of course, he died for the freedom of Greece

Rejoice.